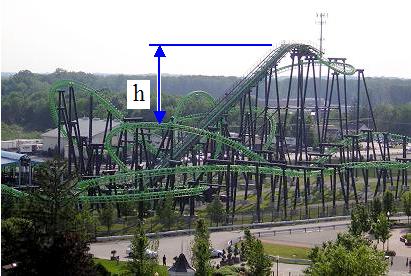

Roller Coaster Physics

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jekert/3089042791

One can best gain an appreciation of roller coaster physics by riding on a roller coaster and experiencing the thrill of the ride. There are many variations on roller coaster design. But needless to say, they all involve going around loops, bends, and twists at high speed.

The typical roller coaster works by gravity. There are no motors used to power it during the ride. Starting from rest, it simply descends down a steep hill, and converts the (stored) gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy, by gaining speed. A small amount of the energy is lost due to friction, which is why it's impossible for a roller coaster to return to its original height after the ride is over.

The roller coaster uses a motorized lift system to return to its original position at the top of the initial hill, ready for the next ride.

The figure below illustrates the concept.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flying_roller_coaster. Author: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GL-X-Flight.jpg

Assuming no friction losses, when the center of mass of the roller coaster falls a vertical height h (from the initial hill) it will have a kinetic energy equal to the gravitational potential energy stored in the height h.

This can be expressed mathematically as follows.

Let W be the gravitational potential energy at the top of the hill.

Then,

where m is the mass of the roller coaster, and g is the acceleration due to gravity, which equals 9.8 m/s2 on earth's surface.

The kinetic energy of the roller coaster is:

where v is the speed of the roller coaster.

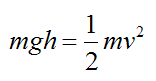

If we assume no friction losses, then energy is conserved. Therefore,

Thus,

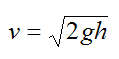

mass cancels out, and

This result is nice because it allows us to approximate the speed of the roller coaster knowing only the vertical height h that it fell (on any part of the track). Of course, due to friction losses the speed will be a bit less than this, but it is very useful nonetheless.

Another important aspect of roller coaster physics is the acceleration the riders experience. The main type of acceleration on a roller coaster is centripetal acceleration. This type of acceleration can produce strong g-forces, which can either push you into your seat or make you feel like you're going to fly out of it.

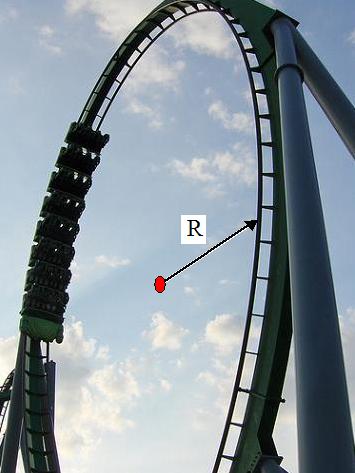

Centripetal acceleration occurs mainly when the roller coaster is traveling at high speed around a loop, as illustrated in the figure below.

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/joeshlabotnik/2479908266

where R is the radius of the loop.

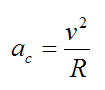

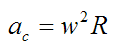

The centripetal acceleration experienced by the riders going around the loop is:

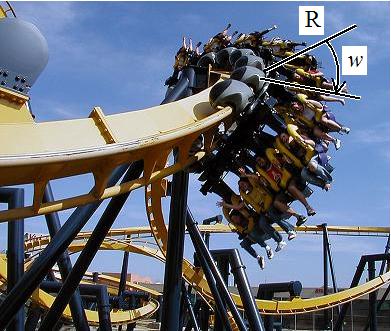

Centripetal acceleration can also occur when the riders twist around a track, as illustrated in the figure below.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roller_coaster_elements. Author: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:BrandonR

The centripetal acceleration experienced by the riders twisting around the track is:

where w is the rate of twist (in radians/second) of the riders as they move along the track, and R is the radius of the twist at the location of the rider.

The acceleration experienced by riders on roller coasters can be quite high, as much as 3-6 g (which is 3-6 times the force of gravity).

In summary, the physics of roller coasters (in general) is a combination of gravitational potential energy converted into kinetic energy (high speed), and using this speed to create centripetal acceleration around different portions of the track.

Return to Amusement Park Physics page

Return to Real World Physics Problems home page

Free Newsletter

Subscribe to my free newsletter below. In it I explore physics ideas that seem like science fiction but could become reality in the distant future. I develop these ideas with the help of AI. I will send it out a few times a month.