Euler Equations

Derivation Of The Euler Equations Of Motion For A Rigid Body

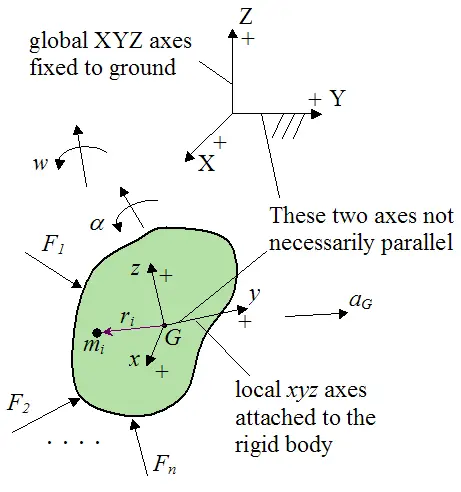

To derive the Euler equations of motion for a rigid body we must first set up a schematic representing the most general case of rigid body motion, as shown in the figure below.

In the schematic, two coordinate systems are defined:

The first coordinate system used in the Euler equations derivation is the global XYZ reference frame. This reference frame is fixed to the ground. It is an inertial reference frame. It is useful to define a global (fixed) reference frame since quantities will only make sense if they are measured from a fixed frame. For example, we can only observe (and make sense of) the change in direction of an acceleration vector over time, if it is measured from a fixed reference frame.

The second coordinate system used in the Euler equations derivation is the local xyz reference frame. This reference frame is attached to the rigid body and moves with it. The origin of this reference frame is located at the center of mass G of the rigid body.

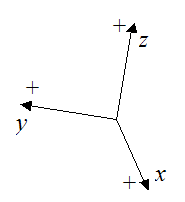

For both reference frames a sign convention is assigned, as shown in the figure below. The derivation of the Euler equations will be based on this sign convention.

For both reference frames, the positive direction of the three individual axes is defined as shown. The choice of positive direction for these axes is important, especially for the local xyz reference frame. For the local xyz reference frame this choice of sign convention affects the derivation of the equations of motion. This is because these equations are derived using vector cross-product multiplication, the mathematics of which is based on this choice of sign convention for xyz. So it is important to use this same sign convention (for the local xyz reference frame) when solving dynamics problems using the equations of motion (such as the Euler equations), since the equations are based on this sign convention. If you use another sign convention, you might get the wrong answer.

For the global XYZ reference frame there are instances where the choice of positive direction for the axes is not important. But instances where the choice does matter are where (for example) cross-product multiplication is used. For example, let’s say we were to calculate the acceleration of the center of mass G of the rigid body with respect to the global XYZ reference frame, using the general vector equation:

This equation involves vector cross-product multiplication, which (as mentioned before) is based on the choice of sign convention for XYZ.

So, even though there are instances where the choice of sign convention for XYZ does not matter, it is not practical to list them all. So to be on the safe side it is better to always use the sign convention shown here for every dynamics problem you solve, using equations of motion (such as the Euler equations). Then you can’t go wrong.

The following variables are used in the derivation of the Euler equations (these are shown in the figure above):

F1, F2,..., Fn are the external forces acting on the rigid body

G is the center of mass of the rigid body

w is the angular velocity of the rigid body with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes

α is the angular acceleration of the rigid body with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes

aG is the acceleration of the center of mass G with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes

mi is a small, arbitrary mass element in the rigid body. This mass element is small enough to be considered a particle

ri is the position vector from the center of mass G to the point where mi is located. This vector is measured relative to the local xyz axes

To begin the derivation of the Euler equations, apply Newton’s Second law to the small mass element:

Where:

ΣFi is the vector sum of the forces acting on the small mass element. These forces are measured relative to the local xyz axes

mi is the mass of this small mass element

ai is the acceleration vector of this small mass element with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes. To calculate this acceleration, one must first determine the acceleration vector ai with respect to the global XYZ axes, and then resolve this vector along the local xyz axes. This is often done using trigonometry.

We can rewrite the vector sum of the forces as

where ΣFext,i is the vector sum of the external forces acting on the small mass element, and ΣFint,i is the vector sum of the internal forces acting on the small mass element.

Therefore,

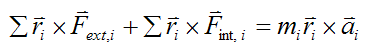

The next step in the derivation of the Euler equations is to take the cross product of both sides of this equation with the vector ri. This gives

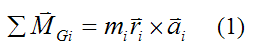

The left side of this equation is defined as the sum of the moments acting on the small mass element mi taken about point G. Rewrite this equation as

where ΣMGi is the vector sum of the moments acting on the small mass element mi taken about point G (this is relative to the local xyz axes).

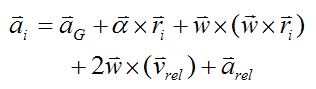

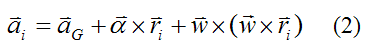

The acceleration term ai on the right side of equation (1) can be rewritten based on the equation for general motion, shown below:

Since the small mass element mi is part of the rigid body and moving with it,

Therefore,

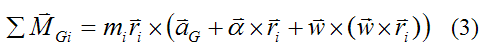

Substitute equation (2) into equation (1). This gives us

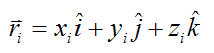

Set:

Where:

xi, yi, zi are the components of the vector ri relative to the local xyz axes

i, j, k are unit vectors pointing along the positive x, y, z axes (respectively)

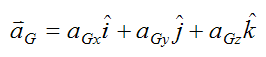

Set:

Where:

aGx, aGy, aGz are the components of acceleration of the center of mass G with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes. To calculate these components, one must first determine the acceleration vector of the center of mass G with respect to the global XYZ axes, and then resolve this vector along the x, y, z directions to find the components aGx, aGy, aGz. This is often done using trigonometry.

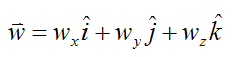

Set:

Where:

wx, wy, wz are the components of the angular velocity of the rigid body with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes. To calculate these components, one must first determine the angular velocity vector of the rigid body with respect to the global XYZ axes, and then resolve this vector along the x, y, z directions to find the components wx, wy, wz. This is often done using trigonometry. Note that wx, wy, wz are constant over the entire rigid body. This means that the entire rigid body moves with a single angular velocity, even though different points in the body might be moving at different linear velocities.

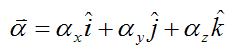

Set:

Where:

αx, αy, αz are the components of the angular acceleration of the rigid body with respect to ground, and resolved along the local xyz axes. To calculate these components, one must first determine the angular acceleration vector of the rigid body with respect to the global XYZ axes, and then resolve this vector along the x, y, z directions to find the components αx, αy, αz. This is often done using trigonometry. Note that αx, αy, αz are constant over the entire rigid body. This means that the entire rigid body moves with a single angular acceleration, even though different points in the body might be moving at different linear accelerations.

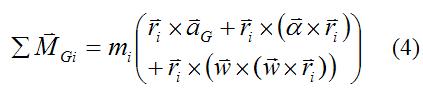

Rewrite equation (3):

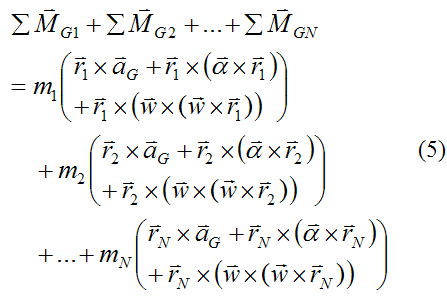

The final step in the derivation of the Euler equations is to sum both sides of equation (4) over all the small mass elements in the rigid body. This sum is as follows:

where N is the number of small mass elements making up the rigid body.

On the left side of equation (5) internal forces cancel in pairs (by Newton’s Third Law), and the result is only external moments remaining (on the left side). The external moments are due to the external forces F1, F2,..., Fn.

It now remains to carry out the messy cross-product multiplications on the right side of equation (5) and then sum the resulting terms using integration (over the rigid body). This will not be shown here, since it is merely a mathematical exercise.

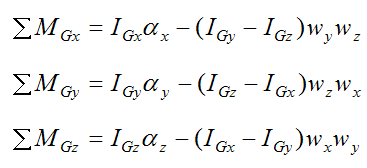

The following (scalar) equations of motion result:

Where:

ΣMGx is the sum of the moments acting on the rigid body, taken about point G and about the local x-direction

ΣMGy is the sum of the moments acting on the rigid body, taken about point G and about the local y-direction

ΣMGz is the sum of the moments acting on the rigid body, taken about point G and about the local z-direction

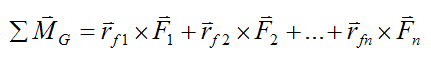

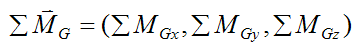

Note that

Where:

ΣMG is the sum-of-moments vector

rf1, rf2,..., rfn are the position vectors from the center of mass G to the locations on the rigid body where the external forces F1, F2,..., Fn are acting. For example, the position vector rf2 is from the center of mass G to the location on the rigid body where F2 is acting. The vectors rf1, rf2,..., rfn and F1, F2,..., Fn are all measured relative to the local xyz axes.

For more information on moments see moment of a force.

Now, we can express ΣMG as its vector components:

where ΣMGx, ΣMGy, ΣMGz are the terms on the left side of the (scalar) equations (6)-(8).

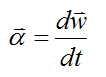

Also, note that

In other words, the angular acceleration vector is the derivative of the angular velocity vector. See vector derivative for more information.

The three general equations (6)-(8) describe the motion of a rigid body at an instant. The Euler equations will follow from these, as will be shown. If any of the variables (such as the sum-of-moments, angular velocity, or angular acceleration) in these equations change, the equations must be re-solved to find the new unknowns (corresponding to the new variables). In general, when solving real-world problems these equations must be evaluated using numerical techniques, such as for the physics of bowling.

The following six terms in the equations are called “inertia terms”. They are a function of how the mass is distributed in the rigid body. These terms are calculated relative to the local xyz axes with origin at point G.

Since the local xyz reference frame is defined as attached to the rigid body (and moving with it), the six inertia terms remain constant as the rigid body moves in space. This is the reason why we define the xyz frame as being attached to the rigid body. Otherwise, the inertia terms will change with time (usually). This would add unnecessary complexity to the problem.

Now, if xyz is aligned with the principal directions of inertia of the rigid body:

As a result, equations (6)-(8) simplify to:

These three equations are called the Euler equations of motion, named after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, who first developed them. They are scalar equations corresponding to the three local x, y, z directions.

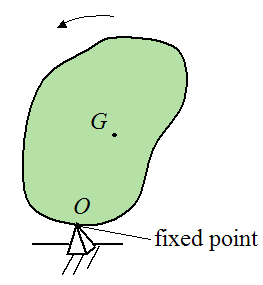

The equations (6)-(8) and the Euler equations apply for moments summed about the center of mass G of the rigid body. And they also apply for moments summed about a point O, where O is a point on the rigid body that is attached to ground (e.g. a pivot). This is illustrated below.

For this situation the inertia terms would be calculated relative to point O.

When using the equations of motion (6)-(8) or the Euler equations to solve dynamics problems, the following applies:

If you know the direction of spin of the angular velocity, you must use the right-hand rule to assign the correct direction for its corresponding vector, and thus determine the correct values for its three components (wx, wy, wz). Similarly, if you know the direction of spin of the angular acceleration, you must use the right-hand rule to assign the correct direction for its corresponding vector, and thus determine the correct values for its three components (αx, αy, αz). The right-hand rule is consistent with the cross-product multiplications carried out in the derivation of the equations of motion, and is therefore consistent with the choice of sign convention shown here, for xyz. This again stresses the importance of using the sign convention shown here when solving problems using these equations. This sign convention is standard in physics books.

The right-hand rule also applies to the sum-of-moments vector (e.g. ΣMG). To determine the correct direction for this vector, you can use the right-hand rule. However, if you are calculating this vector directly using cross-product multiplication (e.g. ΣMGx = Σr×F, where r is the position vector and F is an external force vector), then you do not need to apply the right-hand rule to determine its direction. This is because the resultant vector (calculated from Σr×F), is automatically pointing in the correct direction.

For more information on moments see moment of a force.

The Insight Behind Equations (6)-(8) And Euler's Equations

It is very interesting that one can derive the (somewhat complicated) Euler equations of motion simply from a clever application of Newton’s Second Law (F = ma), and Newton’s Third Law.

The key to deriving equations (6)-(8) and the Euler equations is to take the cross-product of both sides of Newton's Second Law equation with the position vector ri, and then going through the mathematics. But you might be asking, how does one know to take the cross-product in order to derive equations (6)-(8) and the Euler equations? The truth is that there really is no concrete way of knowing beforehand that this is what you should do. It is something that one must "try and see", and then "see what happens". However, since Newton's Second Law equation only allows one to solve for translational motion, we know that we need to develop additional equations that account for rotation as well (since the most general state of motion of a body is translation plus rotation).

Taking the cross-product is simply a way of accounting for rotation. And this is true even if the forces acting on a body cancel out. For example, let's say we have two equal and opposite external forces that are offset a certain distance apart, and are acting on a body. These forces cancel out, which means that the acceleration of the center of mass of the body is zero (By Newton's Second Law). However, the body will still rotate. So there needs to be some way to account for the effect of these two forces on the rotation (since Newton's Second Law, by itself, provides no information on that). Application of the cross-product is a mathematical way of accounting for rotation caused by these two forces. By taking the cross-product of each of these two forces with a position vector (say, from the center of mass of the body to where the forces act), and then summing them together, we find that they do not cancel out. So this alone gives a clue that the cross-product can account for the rotation of a body due to the forces acting on it. And as we have seen, equations (6)-(8) and the Euler equations are the grand result of applying the cross-product to Newton's Second Law equation.

A Further Note On Sign Convention

As mentioned before, equations (6)-(8) and the Euler equations are based on the sign convention used here (i.e. that is how they are derived).

An example of a sign convention that does not match the one used here is shown below.

If you use this sign convention to solve problems using equations (6)-(8) or the Euler equations, you might get the wrong answer!

Return to Dynamics page

Return to Real World Physics Problems home page

Free Newsletter

Subscribe to my free newsletter below. In it I explore physics ideas that seem like science fiction but could become reality in the distant future. I develop these ideas with the help of AI. I will send it out a few times a month.