About me and why I created this physics website.

The Physics Of Running

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Usain_Bolt_winning.jpg

Knowledge about the physics of running is of particular interest to high-level athletes who strive to optimize their performance, using a combination of expert coaching and state-of-the-art training facilities. To most people, the physics behind running is hardly given a second thought. But when medals, such as Olympic medals, are on the line then such thoughts become commonplace and turn into active areas of research.

There has been significant research done in the past on the physics of running, and I will discuss some of the main aspects of it here.

I will first talk about basic running mechanics.

Forces generated during running

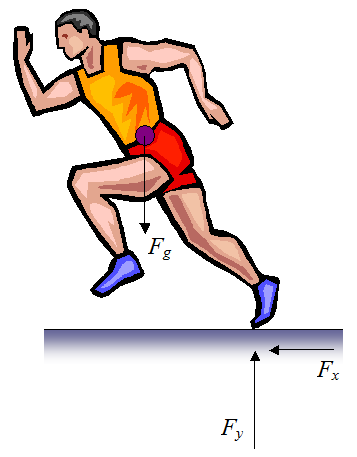

Consider the figure below showing the profile view of a runner on a flat horizontal surface. The forces are indicated.

This figure shows the forces acting on a runner when he is pushing off the ground with one of his feet. The force Fx is the horizontal force due to the contact between the runner's foot and the ground, and the force Fy is the vertical force due to the contact between the runner's foot and the ground. The force Fg is the force due to gravity which pulls down on the runner. This force acts through the center of mass of the runner, represented by the purple dot. During a run the force Fy is greater than Fg in order to lift the runner off the ground as he runs.

The force that drives the runner forward is the propulsive force Fx. Running speed is directly related to the magnitude of this force. An Olympic sprinter can push off the ground with a total peak force of more than 1000 pounds (with a time averaged Fx equal to about 200 pounds, which is less than the peak Fx). In contrast, the average person can apply 500-600 pounds of total peak force. Reference: http://www.thepostgame.com/features/201107/usain-bolt-case-study-science-sprinting

According to Peter Weyand, a science professor at Southern Methodist University, during a sprint the average person's foot is on the ground for about 0.12 seconds, while an Olympic sprinter's foot is on the ground for just 0.08 seconds.

He further states that the amount of time that one's legs are off the ground is 0.12 seconds, regardless if you're fast or slow. He adds that, "an elite sprinter gets the aerial time they need with less time on the ground to generate that lift — or to get back up in the air — because they can hit (the ground) harder." Reference: See above link.

Path traveled by runner's center of mass

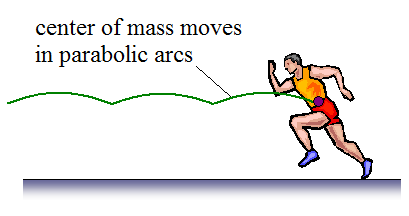

As the runner runs along, his center of mass follows a parabolic arc, as shown in the figure below.

This parabolic path is due to the force of gravity acting on the runner between foot strikes with the ground. These foot strikes propel him through the air in a shallow arc, up until the time he lands with his other foot, at which point he pushes off the ground with that foot, which then sends him once more through the air with his center of mass following a parabolic arc. The force that the runner pushes off the ground with serves as an initial launch force which causes his center of mass to follow a parabolic arc, as predicted by Newton's second law and the equations of projectile motion.

The greater the force Fx, the greater the horizontal running velocity, and the longer the arc length, hence the faster the runner will run.

Arm Swinging

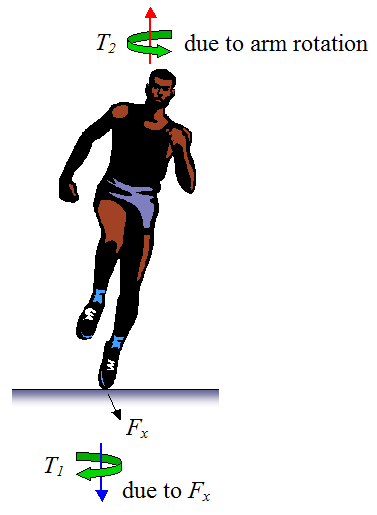

Arm swinging is an important part of running. It serves to stabilize the body. To illustrate this consider the figure below.

As the runner's left foot strikes the ground, he pushes off with a force Fx. This force causes a torque T1 to be exerted on his body which tends to rotate his torso in the direction shown. To correct for this rotation the runner simultaneously swings his arms in the direction shown which exerts a counter torque T2 on his body which tends to rotate his torso in the opposite direction. The generation of this counter-torque helps keep his body stable and facing forward as he runs.

Similarly, When his right foot strikes the ground the situation reverses, and his arms must swing in the opposite direction to before to induce a corrective torque which once more helps keeps his body facing forward.

Keeping your arms bent while running makes it easier to swing them. Think of a swinging pendulum. A short pendulum is easier to swing than a long pendulum, and by analogy your arms are easier to swing when they are bent.

When we run we do all this without thinking. It is a completely automatic set of movements.

Let's now look at some optimal running strategies as given in the literature.

Case 1 – Optimal running strategy for short sprints less than 291 meters [1, 2]

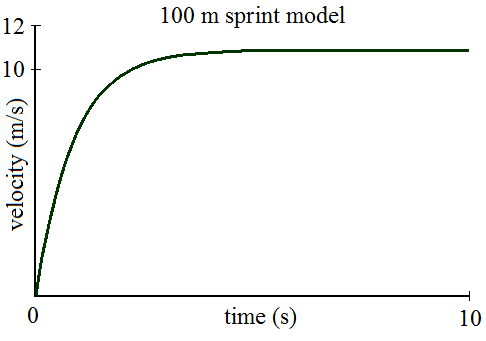

According to an analysis given in reference [2] (and based on the physiology of record holders from 1973), the distance of 291 meters is a transition point in the optimal running strategy. For distances less than 291 meters, the runner should accelerate as fast as possible until he reaches his maximum speed. He should then maintain this speed until the end of the race. The figure below illustrates this for a typical 100 meter men's sprint:

The mathematical equations for this optimal running strategy are given in an ebook, the details of which are described below.

Case 2 – Optimal running strategy for a race longer than 291 meters: The 400 meters [1, 2]

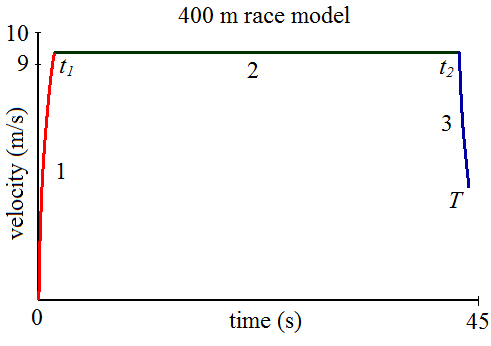

According to an analysis given in reference [2] (and based on the physiology of record holders from 1973), the runner should accelerate as fast as possible for 1.78 seconds. This will enable him to reach a speed near his maximum. He should then maintain this speed for as long as he can. This speed will be such that 0.86 seconds before the end of the race his energy is entirely used up, and after this point is reached his running speed will begin to drop. Clearly this would be difficult to exactly reproduce in an actual race but it does give some non-intuitive insight into how 400 meter sprinters might maximize their performance. The figure below illustrates this for a typical 400 meter men's race:

Where t1 and t2 are intermediate times representing the start and end of the cruising (constant speed) stage. T is the time at which the race ends. Now, t1 = 1.78 seconds, and t2 = T − 0.86 seconds. This is based on the physiology of record holders from 1973.

The numbers 1, 2, 3 represent the three stages of the race: The acceleration stage (1), the cruising stage (2), the deceleration stage (3).

The mathematical equations for this optimal running strategy are given in an ebook, the details of which are described below.

For races that are greater than 400 meters the strategy to use is less clear [1].

According to reference [1], "There is typically an acceleration in the later part of the race, either quickly and forcefully to defeat competitors, or gradually over the final third of the race to expend all remaining energy more evenly."

In the absence of a good physical model to assist runners in their racing strategy, they must ultimately rely on "feel"; which is a combination of psychological factors based upon their positioning relative to other runners, and how their body feels as they settle into the race.

Effect of race curve on running times

Sprinting around a turn (such as for the 200 m and 400 m races) is known to result in a longer race time than if the race were run on a straight track. This is due to the centripetal force experienced by the runner as he goes around the turn. This has the effect of diminishing the force available to the runner for propelling himself around the track. As expected, this effect is more pronounced the smaller the turn radius is. Hence we have the common complaint by runners that the inside lane is "too tight".

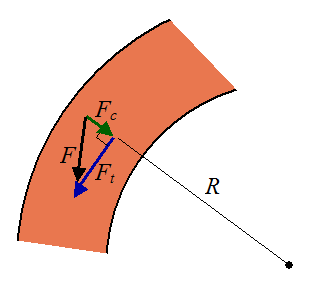

The figure below shows the contact forces acting between the runner's foot and the curved track. The turn radius is R.

Running around a turn forces the runner to produce a centripetal force Fc in order to maintain his curved running path around the track. This centripetal force is in addition to the force necessary to propel him tangentially along the track, which is Ft. The total force F (exerted by the track on the runner) has components Ft and Fc.

In reference [3], the authors determine that a runner in lane 1 (the innermost lane) would run the 200 m in 19.72 seconds, whereas in lane 8 (the outermost lane) he would run it in 19.60 seconds. This is a big time difference and translates into a distance of about 1 meter at the finish line. Since many races are won or lost be mere centimeters, this is a very significant difference. However, it should be pointed out that sprinters do not consider lane 8 to be the most advantageous one either since, due to the staggered starts, they would run half the race ahead of the other runners which puts them in a psychological disadvantage of not being able to see what the other runners are doing.

Effect of track material on running times

It is possible to lower world record running times by selecting an optimized track material. An optimized track would have a certain amount of stiffness built into it, based on the mechanical properties of the human runner. The track stiffness is much like the stiffness of a spring. And the stiffness should not be too much or too little. It must fall within an optimal range. This optimal range should be such that, during a runner's foot strike, the track efficiently absorbs energy (during the penetration stage), and releases this same amount of energy (during the rebound stage).

I have available a 10 page ebook, in PDF format, which gives more information on the physics of running, based on a literature review. It includes the mathematical equations of case 1 and 2, the mathematical equations of running around a curve, and a mathematical equation for predicting long distance running records for distances greater than 2000 m. It's available through this link.

References

1. Dan Whitt, Mathematical Models of Running, UMS talk, September 24, 2008. http://www.stanford.edu/~dwhitt/UMS-talk.pdf

2. Joseph B. Keller, A Theory of Competitive Running, Physics Today 26(9), 42-47 (1973).

3. Igor Alexandrov and Philip Lucht, Physics of Sprinting, American Journal of Physics 49, 254-257 (1981).

Thought Provoking Bonus Material

Is running better than walking to keep dry in the rain?

I created a physics analysis for this problem, in PDF format. It's available through this link.

Return to The Physics Of Sports page

Return to Real World Physics Problems home page